By Deepak Chopra, MD FACP and Mark L. Zeidel, M.D

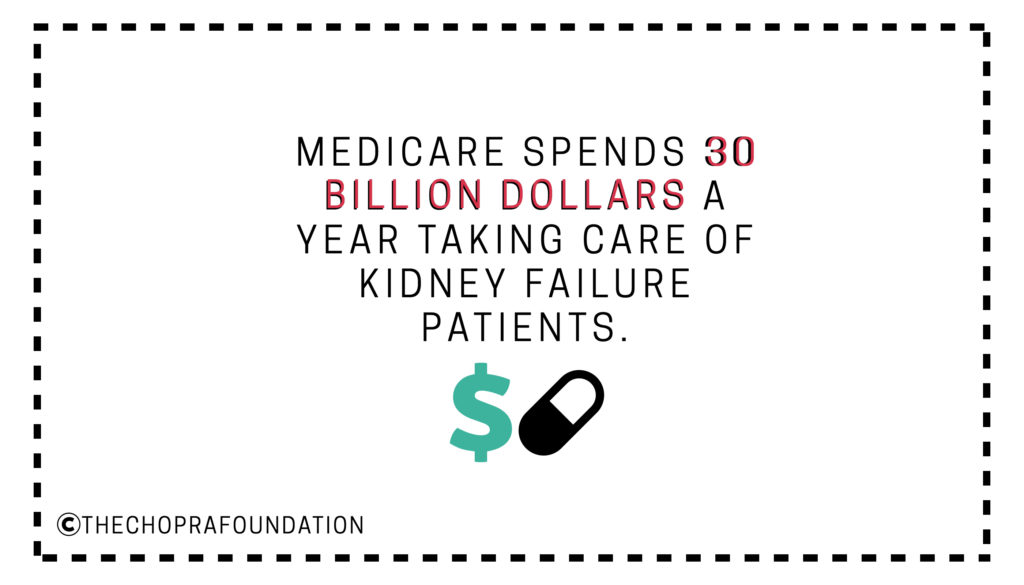

Some diseases make headlines, pull at our heart strings, and inspire high-visibility fundraising events. Others, like kidney disease, wreak havoc more quietly. Chronic kidney disease afflicts more than 26 million people in the U.S., putting them at high risk for other serious illnesses, like heart disease. Nearly half a million people suffer from end-stage kidney disease, a devastating condition often requiring dialysis or transplantation. Medicare spends more than 30 billion dollars a year taking care of kidney failure patients—about 6 percent of the Medicare budget.

While kidney disease is widespread, it disproportionately affects certain populations: African Americans and others of recent African ancestry are more than three times as likely to suffer from kidney failure as those of European descent. African Americans constitute 35 percent of all patients receiving dialysis for kidney disease, despite being only 13 percent of the U.S. population. Some of this disparity is attributable to the most common causes of kidney disease: diabetes and high blood pressure, both of which are more prevalent among African Americans. But there’s increasing evidence that genetics may also play a significant role in the disease. Researchers at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) and elsewhere have discovered that two common variations in a gene called apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) are responsible for an increased susceptibility to several forms of non-diabetes-related kidney disease among African Americans.

Thirty percent of African Americans carry these particular mutations, and for much of human history this served them well: This genotype is actually protective against a disease called African Sleeping Sickness, caused by certain forms of African trypanosomes. Transmitted by the tsetse fly, African Sleeping Sickness is common in eastern Africa and can cause fever, anemia, and death from neurologic disease. While these variants may still be of some benefit to populations living in Africa and exposed to the tsetse fly, here in the U.S. the genetic variation has little benefit and carries significant risk, particularly since there is no cure for kidney disease. As Martin Pollak, MD, Chief of Nephrology at BIDMC, explains, “We have treatments like dialysis and kidney transplants to keep those who have advanced kidney disease alive longer, but we don’t have any cures.” He adds, “Fewer than 40 percent of patients on dialysis live more than five years.” (And in developing countries, even these treatments are often too expensive to be available.) Pollak’s hope is that the APOL1 discovery—part of a body of research that earned him election into the prestigious National Academy of Sciences—will help pave the way toward prevention and treatment of the disease.

To that end, the BIDMC investigators—among the top researchers on kidney disease in the world—are using every scientific tool at their disposal. They’re developing human, mouse and fish models to better understand the genetics, cell biology and biochemistry of APOL1’s action in the kidney. Pollak and his team are also trying to understand why certain carriers of the APOL1 mutations are more susceptible to kidney disease than others. “That might give us some clues on how to better treat the condition,” he says.

In terms of patient care, their research has begun to inform clinical practice. Increasingly, doctors are debating the merits of genetic screening and counseling for those at highest risk of carrying the APOL1 gene mutation. However, until more is known about how to prevent and treat this form of disease, the benefit of testing is unclear. Based on this work, the hope is that specific methods for preventing and treating APOL1-associated kidney disease will be developed and implemented in the coming years.

“We want to put our own division out of business by preventing this disease to begin with,” Pollak says. “Short of that, we’d like to develop treatments that allow people with kidney disease to live with it as a chronic disease.” Until recently, he explains, kidney disease was much like HIV/AIDS was in the 1980s—a terrible disease that devastated lives and perplexed biomedical researchers. Once the causative organism, the HIV virus, was identified, combinations of drugs were developed, which now suppress the virus effectively. “With the discovery of APOL1, this major form of kidney failure now has a cause, and we can develop treatments directed to fixing the causal problem,” Pollak explains. “With a clearer understanding of the underlying genetics, we’re hopeful that kidney disease will soon be like AIDS—a treatable condition with which people can live long and active lives.”

Deepak Chopra MD, FACP, founder of The Chopra Foundation and co-founder of The Chopra Center for Wellbeing, is a world-renowned pioneer in integrative medicine and personal transformation, and is Board Certified in Internal Medicine, Endocrinology and Metabolism. He is a Fellow of the American College of Physicians, Clinical Professor UCSD Medical School, researcher, Neurology and Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and a member of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. The World Post and The Huffington Post global internet survey ranked Chopra #17 influential thinker in the world and #1 in Medicine. Chopra is the author of more than 85 books translated into over 43 languages, including numerous New York Times bestsellers. His latest books are You Are the Universe co-authored with Menas Kafatos, PhD, and Quantum Healing (Revised and Updated): Exploring the Frontiers of Mind/Body Medicine. www.discoveringyourcosmicself.com

Mark Zeidel, M.D., is Herrman L. Blumgart Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Physician and Chief and Chair of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He has made important contributions to our understanding of how the kidney helps control body chemistry, and has led several successful national initiatives in medical education.A national thought leader in quality improvement, he has pioneered the provision of highly reliable, cost-effective care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), where he helped BIDMC’s achieve of outstanding clinical outcomes, recognized by the American Hospital Association, Society for Critical Care Medicine, the Leapfrog Group, and the Department of Health and Human Services. He has received numerous awards, including election to the American Society of Clinical Investigation and the Association of American Physicians, the Robert H. Williams Distinguished Chair of Medicine Award from the Association of Professors of Medicine and the Robert Narins Award for Medical Education from the American Society of Nephrology.